According to the medical school of Monash University, sex refers to the inherent biological differences between men and women, specifically the “chromosomes, hormonal profiles, internal and external sex organs” while gender describes the “characteristics that a society or culture delineates as masculine or feminine”. In other words, a person’s sex does not parallel his gender role in society. For Song, appearing as subservient, modest and vulnerable gave a boost to his femininity which fuelled Gallimard’s willingness to accept him as a woman, as he/she embodies the natural extensions of Gallimard’s perceptions of the Oriental woman. After gulling Gallimard into thinking that he has snared a Chinese Chio Chio San, Song first convinces Gallimard, before crushing his fantasies by destabilizing any gender and racial expectations that Gallimard holds of him. Song’s successful presentation of the Oriental cannot be singularly attributed to his understanding of Western man, but also Gallimard’s naivety and constant seeking of reassurance for his male pride. With his confidence and his career depending critically on Song’s continual submissive act, Gallimard lives in self-denial and refuses to confront the real world effects of his geisha reverie.

The adoption of the name Rene is one of great significance as Rene is a unisex name that does not echo manliness. Portrayed to be an incapable, impotent beta male in his own White culture, Gallimard’s masculinity is repeatedly contested in the play through the depiction of Helga and Renee, the bold White women that he has relationships with. In Song he finds solace as his masculinity is reassured and reinforced as he finally feels “the absolute power of a man”. The seeming psychological abuse that he imposes on Song, by leaving him/her wanting, appears to be a self-serving mentality boosting his ego and pride, thus creating the illusion that he is finally a whip in the East, when he is nothing but a wimp in his own culture. We see a foreshadowing of the complete role reversal between masculinity and femininity through the action of Gallimard pouring tea for Song. This traditional subservient feminine act is pursued out of relief at the arrival of Song, thus assuring the continuation of his fantasy. It is ironic that he achieves consolation of his manhood through these feminine acts just so the object of his fantasy will stay by him. Gallimard is flawed as he is weak mentally and delusional, traits that are traditionally associated with the idea of femininity. The fluidity of gender identities parallels that biological make-up is not a limiting factor, as shown by Song’s female persona and Gallimard’s feminine tendencies.

Despite Song’s extraordinary masquerade as a woman, his act is regularly penetrated by his masculine traits in the way he dictates the thoughts and actions of Gallimard through manipulation for what he cannot achieve explicitly. His vocal intrusion throughout the play amplifies his presence on stage, implying that he is unable to totally fulfil Gallimard’s expectations. Even when he tries hard to fit the image of the perfect Oriental woman, he cannot disregard his inherent nature of want of control. This dispels the belief that Asian men are subpar and more effeminate in comparison to the dominant White male.

The play also presupposes Orientalism as an existing and present concept. The temporal fulfilment of Gallimard’s Orientalist fantasy upheld the relationship between the two characters. Through stereotypes shaped by his own illusions about the Orient, Gallimard succumbs to the notion of the mysterious and erotically exotic as they act like a shortcut to his understanding and interpretation of the Asian culture. By dissolving the barriers to the diversity of cultural boundaries, Gallimard limits his knowledge about the operatic tradition of actors assuming the role of actresses in opera houses due to it being an artistic matter, thus allowing for the careless mistake of misjudgement of identity. Song’s overt portrayal of the Orient character then acted in his favour by skewing Gallimard’s opinions towards him. Gallimard’s obsession and total absorption with the imagined realm of his Butterfly, and his fictitious perception of reality consumes him, perpetrating his self destruction and eventual downfall.

The self proclamation by Song that he is “an Oriental” and thus can “never completely be a man” is also out of character. Orientalism is seen as a derogatory and dehumanising term used by the West in their misconceptions of the East. It reflects a whole spectrum of Western attitudes and prejudices against the Asian race and its culture. It is also atypical that a man questions his male authority and manhood with the conclusion that he does not make the cut and therefore does not encompass the quality of the male race. As such, a lack of self-respect and the act of self-degrading is reflected and the audience is left to wonder about the mental stability of a person who is willing to hide his manhood for twenty years when even his colleague is unable to identify with him, calling him belittling and offensive terms like “homos” and “pervert”. Song’s hollow victory at the end did little to lift him out of the reductive category of Orientalism. It seemed that even though in the play Hwang constantly criticises Western ideals of Asians and tries to dispel the images of the Asian race being mere play things for the West, portraying Song to be a cunning, manipulative man that will stop at nothing, even by putting himself down to the lowest just to achieve his warped means may not be the best way to do so. It acted to reinforce the stereotype of the Orient race and merely offers a repositioning of the marginalised at best.

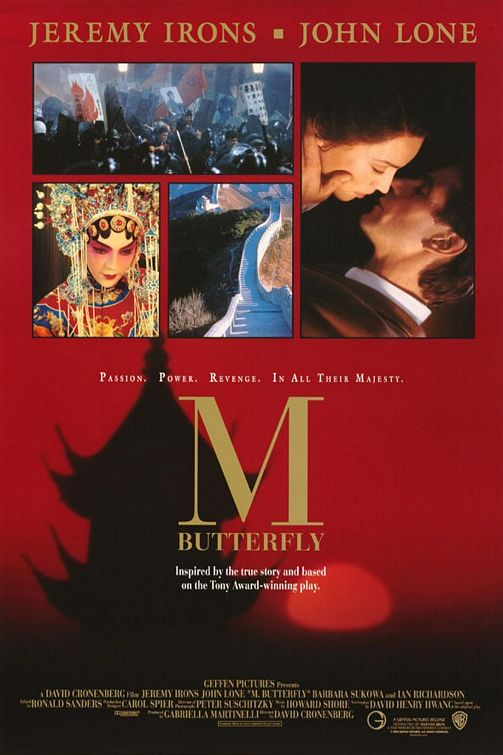

In M Butterfly, it is clear that perceived notions of sex and gender fail to address the issue that biological make-up is not a good reflection of gender identities as one can always counter stipulated roles and expectations through the avenue of drag and deception. The ideals of Orientalism give Western men the hope that there is a Chio Chio San reincarnated out there for his taking. In this case, it acts to butter up Gallimard’s ego and pride so that he thought more highly of himself than what society deems of him, thus luring him into a false sense of security. When forced to confront the disturbing truth of his transvestite act, Gallimard chooses to commit suicide to keep his heterosexual union and fantasies of the Orient intact.

No comments:

Post a Comment